1.0 History of CG

On 20 September 1985, CGT was introduced by the Hawke/Keating[1] government. Events after that date attract CGT while events before are not subjected to CGT. Howard/Costello[3] thought the CGT discount would motivate households to invest in shares and lower the cost of capital[4].

2.0 Cost and Benefits of CGT Discount

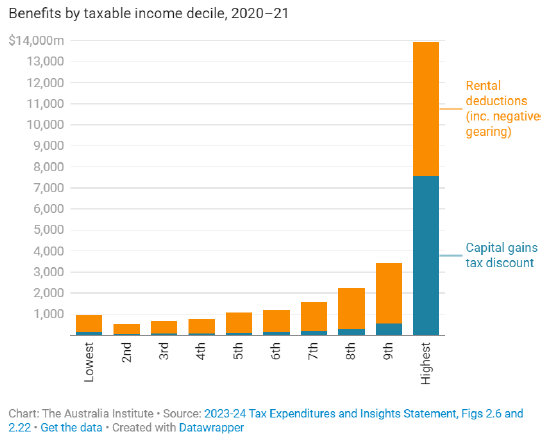

The 50% CGT paired with negative gearing[5], provides a huge incentive for taxpayers (TP) to invest in residential property on a geared basis as the tax advantages are huge. Furthermore, the gearing available to property investors (up to 90% of LVR[6]) is much higher than that available to other investments, such as stocks (average LVR of 50% or less). This generated a huge incentive for ordinary Australians to invest in residential property. However, this benefit primarily flowed to the top 2 deciles of the population as seen below:

Both negative gearing and the CGT discount attributed to property investments are estimated to cost the budget 5.7b and 5.22b respectively, for FY2024[7] , which is 38.6% of the projected FY25 budget deficit[8]. This is expected to grow to 14.5b and 8.35b in FY2035.

While attempting to encourage capital formation and to substitute the loss of indexation, Howard/Costello have inadvertently created a policy that mainly benefits the rich at the expense of the poor.

3.0 Housing Affordability

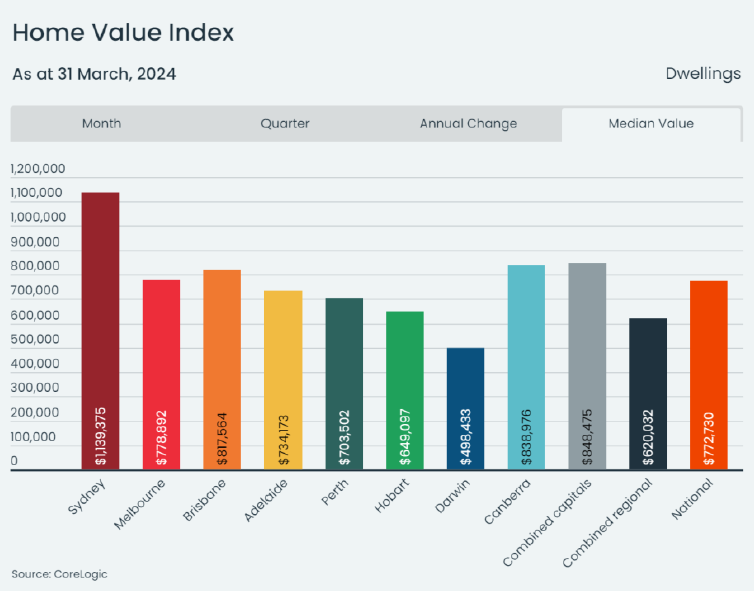

CoreLogic National Median House Values:

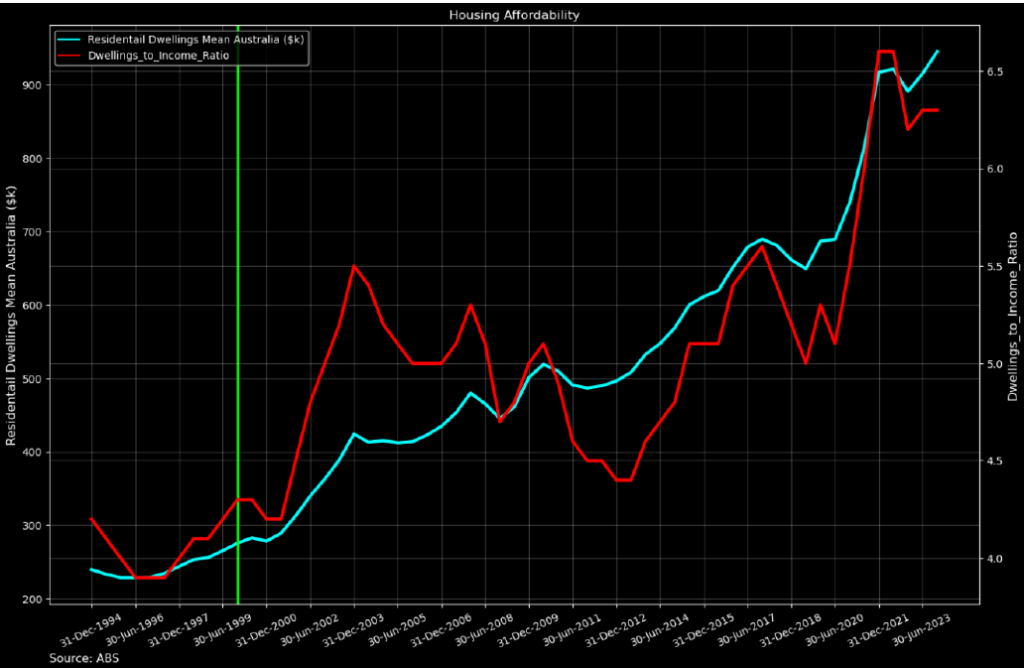

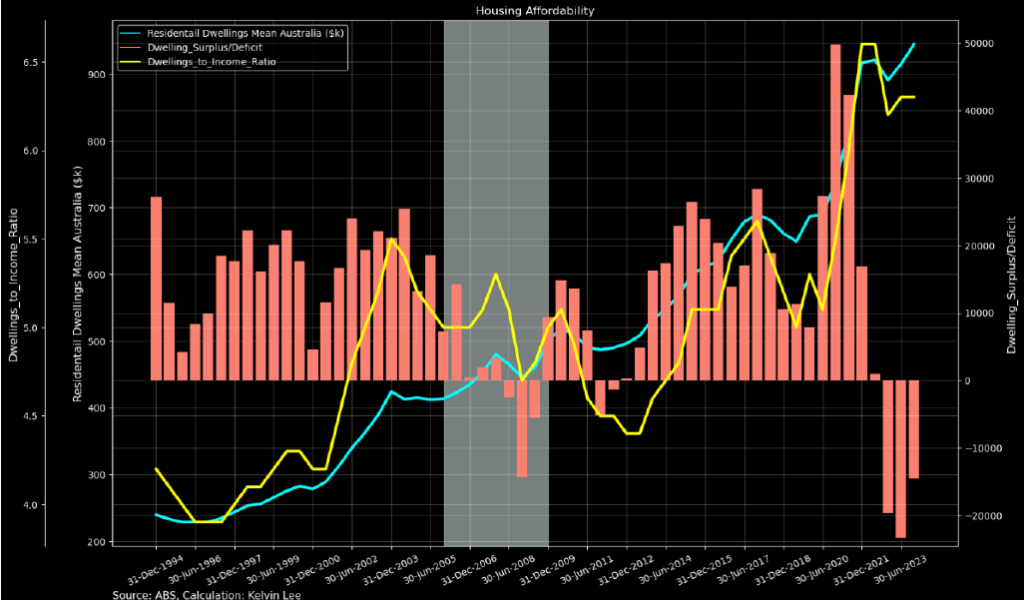

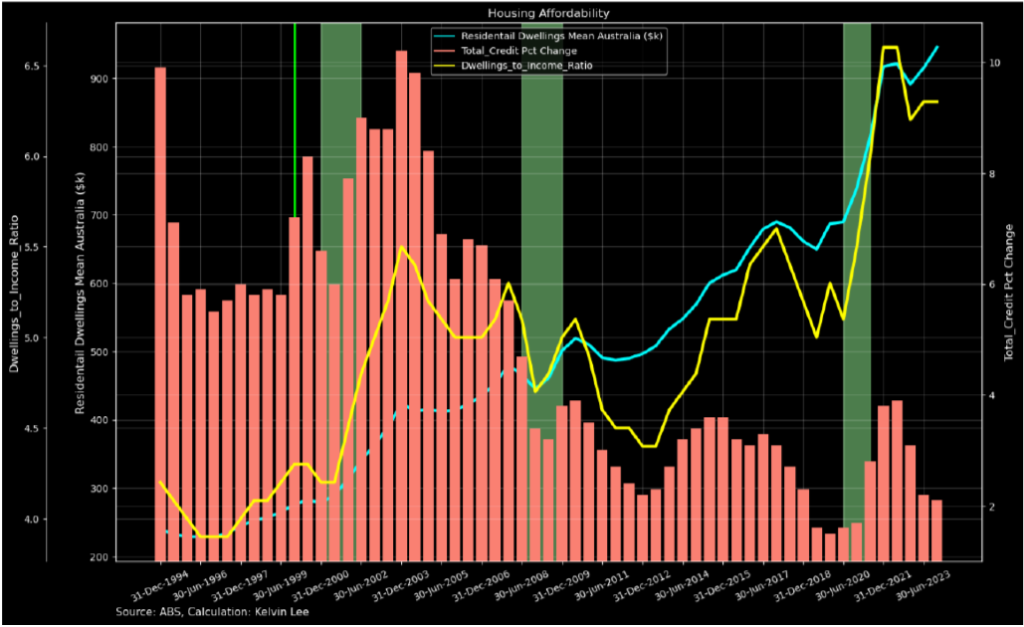

The housing affordability metric most commonly used is the dwelling-to-income ratio (DIR) which is the average dwelling price divided by the average household income, assumed to be 2 individuals on average annual wage[9]. This is seen as the red line in the graph below, with the blue line being the average residential dwelling mean price in Australia and the green vertical line, the date that CGT discount was introduced.

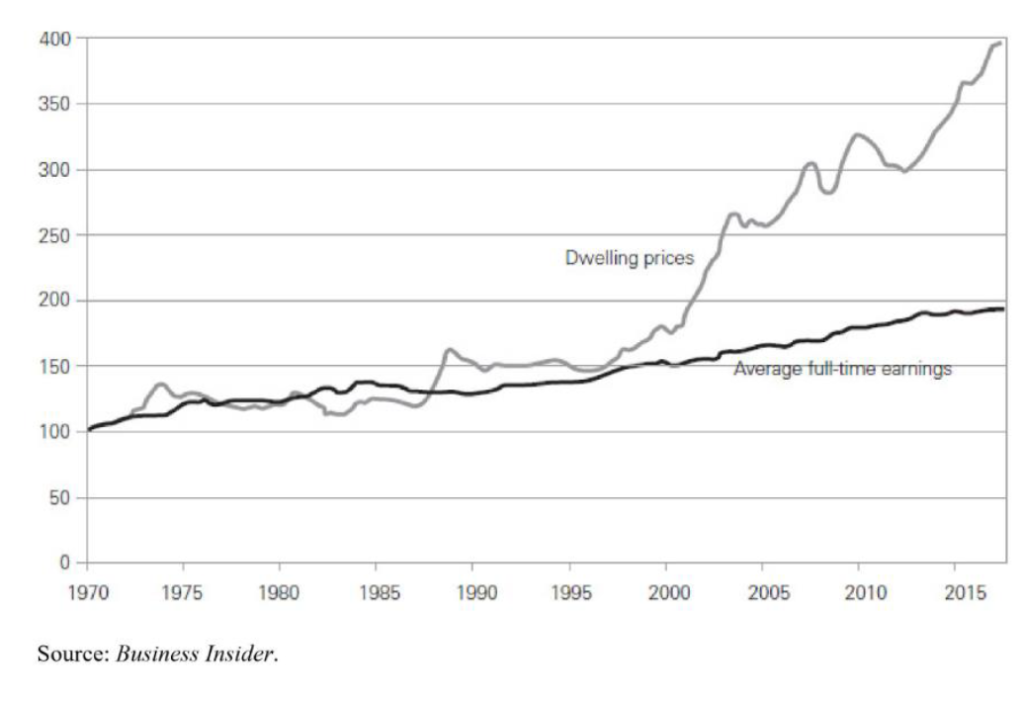

This phenomenon of dwelling prices outstripping wages is only prominent from the mid to late 1990s

4.0 Drivers of House Prices

In the following section, we will examine the 4 common factors affecting dwelling affordability, the literature review around it, and the empirical evidence through the lens of the dwelling-to-price ratio reaction to each factor.

4.1 Migration

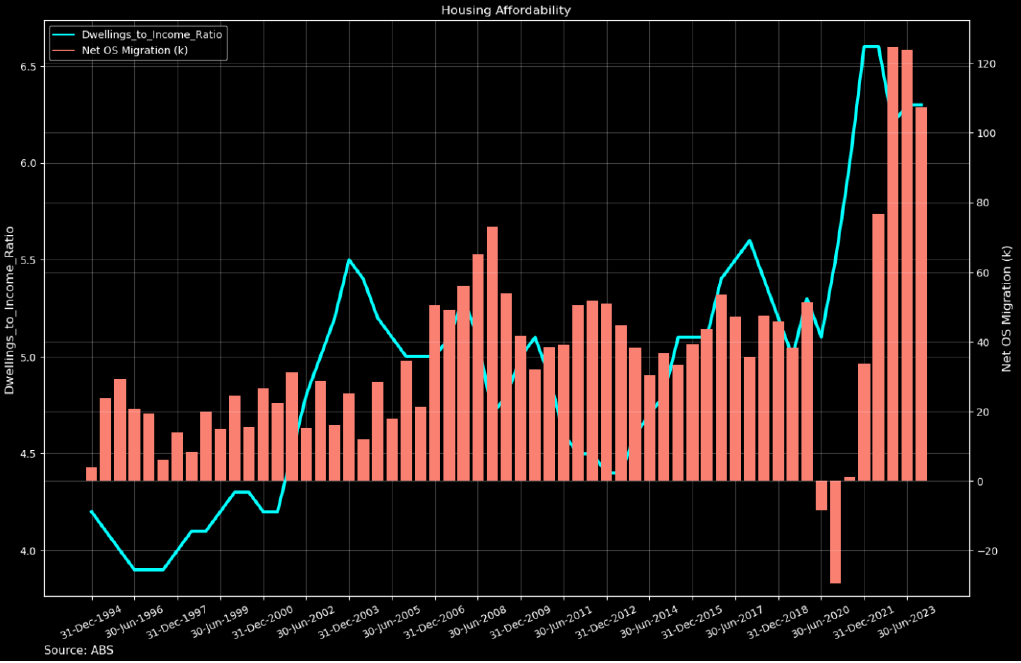

Net overseas migration (NOM) is one of the purported key drivers of dwelling price inflation. NOM remained steady between 1948 to 2003 but doubled between 2005 and 2020[10]. According to ABS data, NOM averaged 48k p.a to 2003 and jumped to 106k p.a after 2003 supporting Kohler’s[11] claim.

Just looking at NOM alone is inadequate, as housing supply[12] plus domestic births and deaths need to be added back for a true picture of a dwelling surplus or deficit. Furthermore, we have factored in building demolitions as well[13].

The grey vertical highlighted area in the graph above is where there is an acute supply deficit, which corresponds to the huge jump in NOM. Dwelling price rises were similar to trend growth during this period and the DIR was stable through this period, which is strange, considering a huge jump in migration and the dwelling deficit. Dwelling prices should have jumped higher than trend growth for the supply deficit, but the data does not support this conclusion.

4.2 CGT 50% discount and Negative Gearing

Dailey et.la[14] calculates that halving the 50% CGT benefit and limiting negative gearing to passive income would decrease housing prices by 2%. They point to some side effects of this policy such as TP holding onto property for longer periods to avoid crystalising CGT. However, Falinski[15] argus that the wave of investor activity should have seen an equivalent wave of supply into the market to meet this demand. None of the authors provide any strong evidence supporting their arguments.

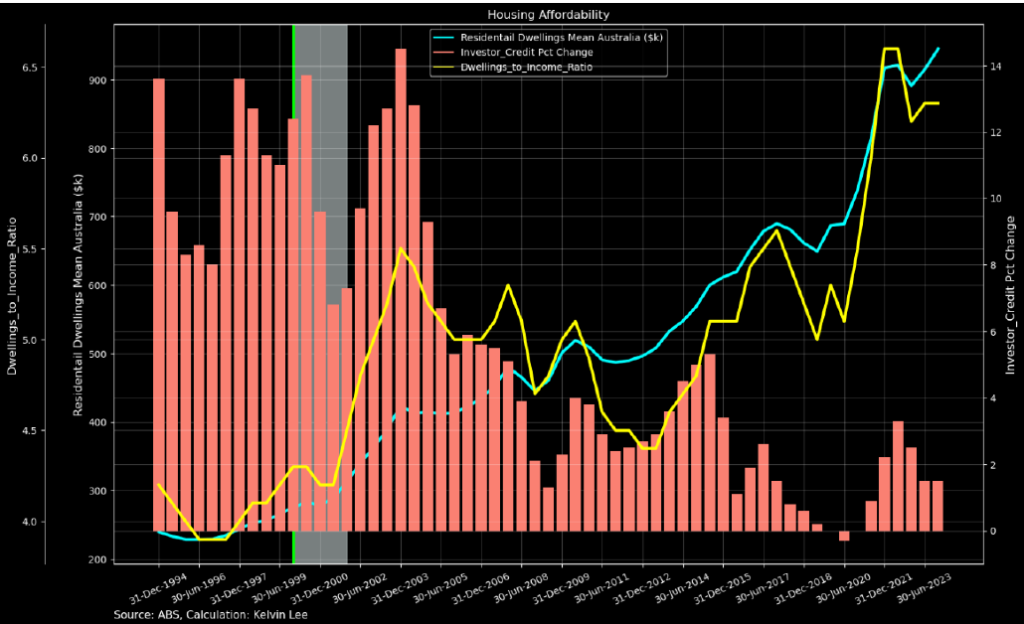

Our approach analyses investor period-on-period (PoP)[16] credit growth to the introduction of the 50% CGT discount. The introduction of the 50% discount should have sparked a wave of investor credit growth.

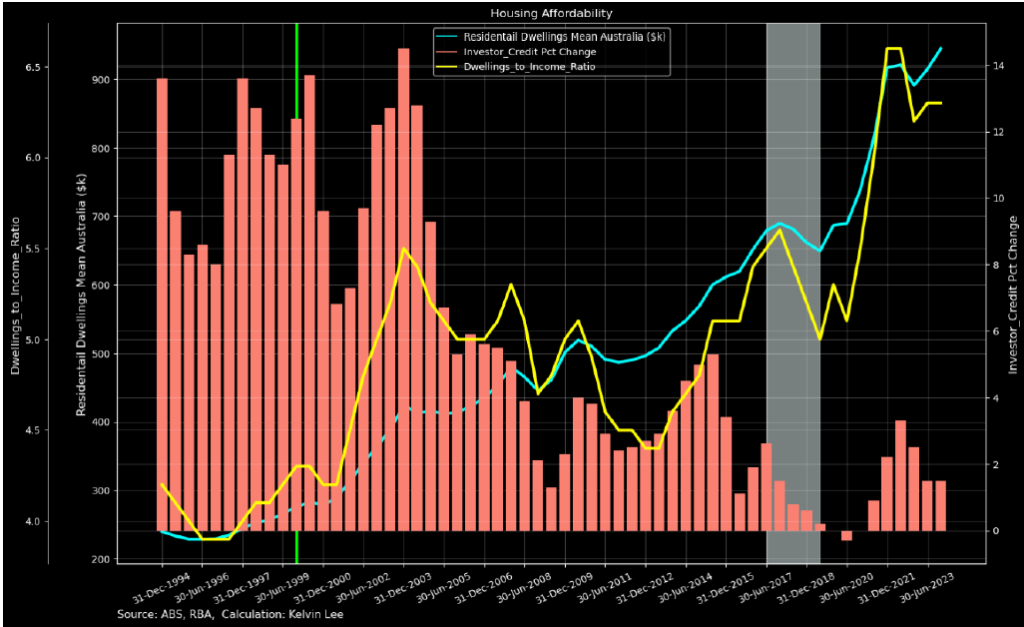

The green vertical line represents the introduction of the 50% CGT discount. While we did see a rise in investor credit on a PoP basis for the next period after the 0% CGT discount introduction, the rise was not large or out of the ordinary with other periods. Furthermore, during the next 2 years (highlighted area above), investor credit growth slowed, dwelling price growth was below trend and DIR dropped. From the lens of DIR, 50% CGT discount does not look to be a determining factor in dwelling prices.

Furthermore, when APRA limited investor loan growth in 2014, constricting the supply of credit, investor credit growth collapsed (highlight area above)[17]. This caused dwelling prices and DIR to fall. Although this is just one sample, credit availability does seem like a plausible factor in determining prices and DIR.

4.3 Fiscal Injections: First Home Buyer Grant (FHBG)

After the 50% CGT discount was introduced together with the GST[18], Howard faced pressure on the electoral front and in July 2000, he introduced a $7k first home buyers grant without a means test. He increased this to $14k in March 2001. It dropped to 11k in December 2001 and finally back to $7k in June 2002. This was a direct fiscal injection into the residential housing market.

During the GFC[19] from October 2008 till June 2009, Rudd[20] increased the FHBG back to $14k with a special tier of $21k for newly built homes[21].

Finally, COVID fiscal injections, such as Job Keeper, which injected $89b (4.5% of 2020 GDP) into the economy, together with second-round Job Seeker top-ups, injected a further $66b into the economy, could be construed as quasi-FHBG, as consumer spending was limited during the lockdown, forcing stimulus into the housing market.

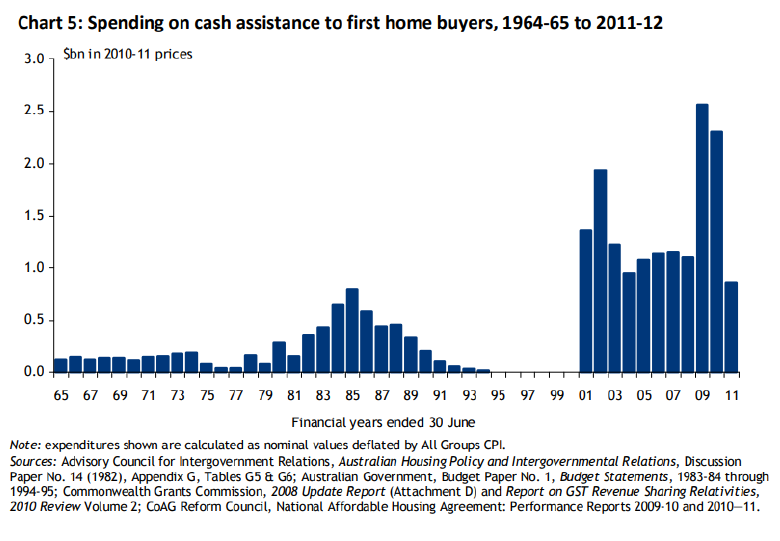

Eslake has been a fierce critic of government housing policy and their obsession with FHBG[22]. He shows a huge jump in fiscal injections into housing post-2000 as seen below.

In our analysis, all 3 periods mentioned above (highlighted) have resulted in a rise in PoP total credit growth, dwelling prices and DIR, during and after.

Anecdotally, this has been the best factor so far in explaining dwelling prices and DIR, corroborating Eslake’s findings.

4.4 Rezoning and Density Limits

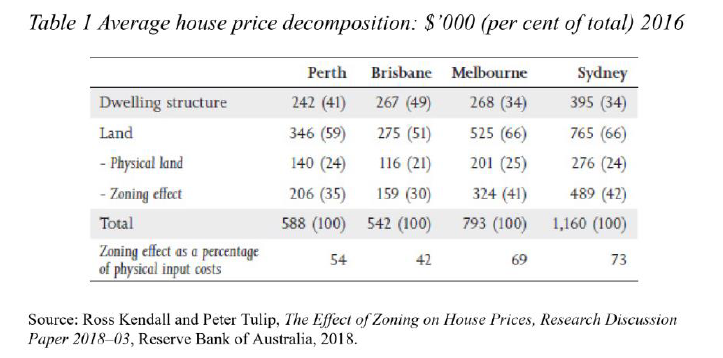

There is general agreement in the literature that rezoning and increasing density would alleviate the supply constraints and increase dwelling supply. Kendall has postulated that zoning has the following impact on dwelling values[23].

As councils control zoning and represent their constituents, who do not want to see increased density in their suburbs (NIMBY-ism[24]), they act like a cartel restricting supply and drive up prices. There have been greater federal and state-level initiatives to build more houses[25], but there has been a lack of details on council-level initiatives. Furthermore, there is no study in Australia to show the efficacy of such a program in improving the DIR.

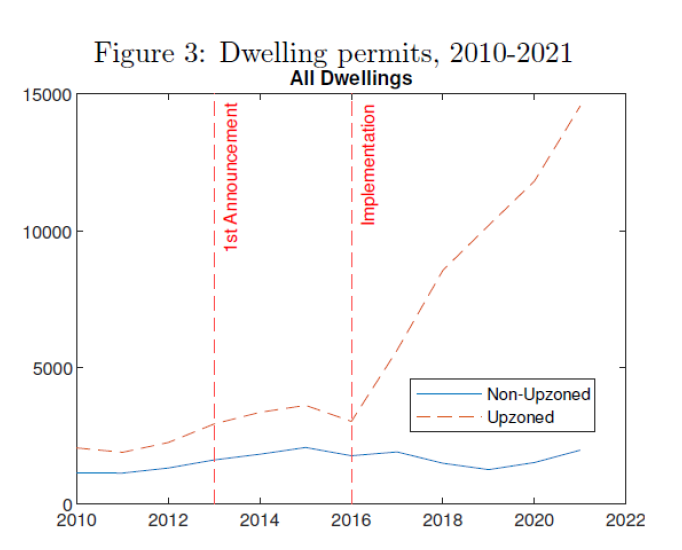

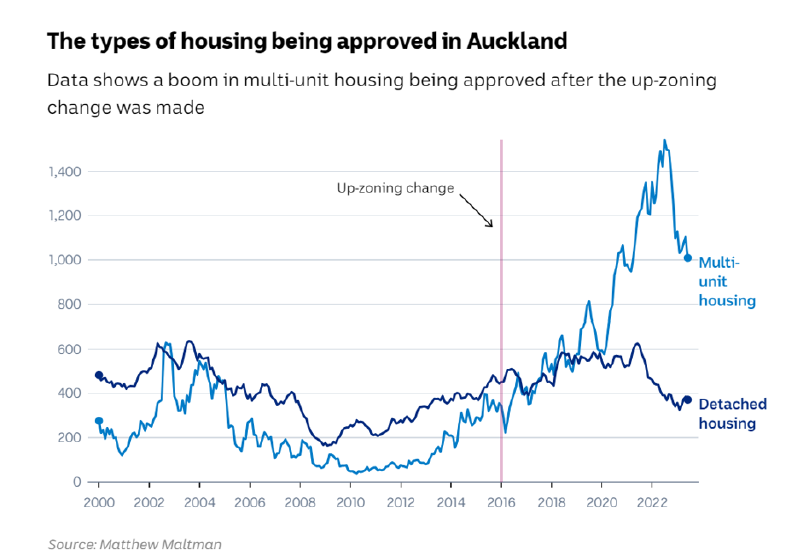

An example of upzoning that can be examined is Auckland’s 2016 policy, where they upzoned three-quarters of Auckland’s residential area[26]. This has increased dwelling permits in upzoned areas as seen below[27].

Increased multi-unit housing availability:

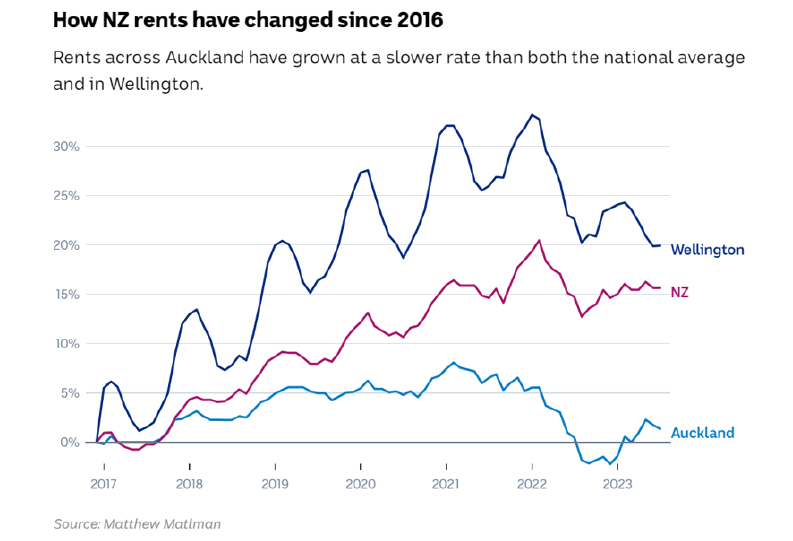

And lowered rents:

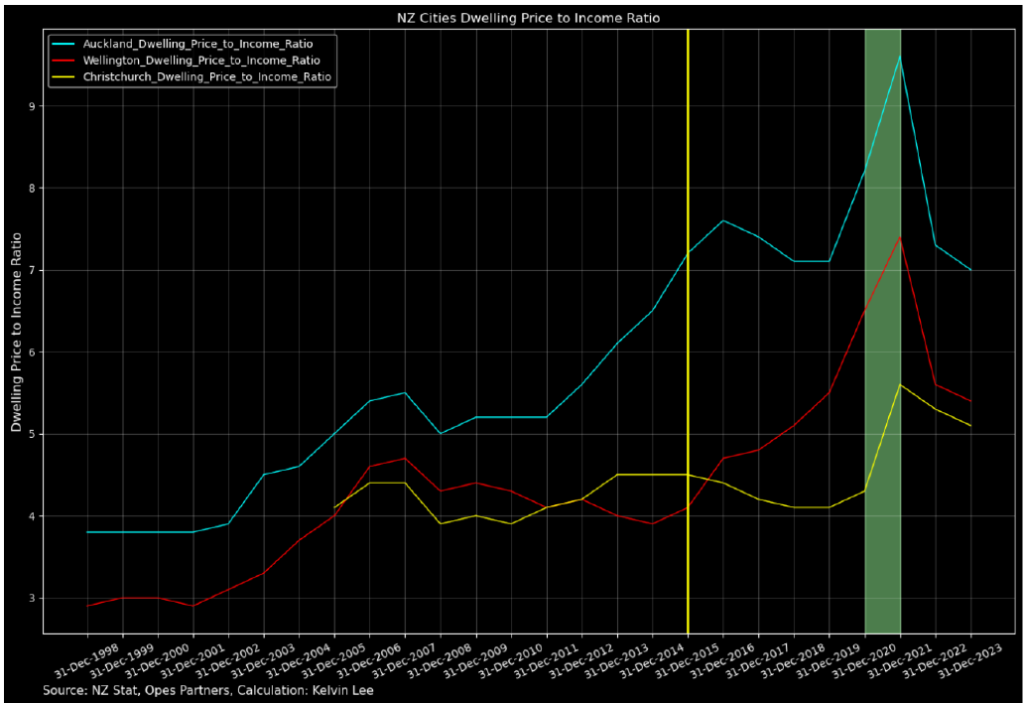

Finally, it slowed dwelling price appreciation in comparison to Wellington and Christchurch.

The yellow vertical line above is the beginning of Auckland’s upzone policy, which seemed to have stopped the rise in its DIR. Covid stimulus by the NZ government, highlighted in green, drove up DIR, but perhaps rezoning has increased supply elasticity in Auckland, allowing the DIR to come back at a faster pace in comparison to the other 2 cities. As this is a one-sample study, its difficult to know.

5.0 Conclusion

From our analysis, through the lens of DIR and its reaction to the four factors presented, on the balance of probabilities, direct fiscal injections seem to be the primary diver of housing affordability

[1] Bob Hawke/Paul Keating.

[2] Indexed to the consumer price index (CPI),

[3] John Howard/Peter Costello

[4] Kohler, A. (2023) The Great Divide Australia’s Housing Mess and How to Fix It; Quarterly Essay 92. Black Inc. Available at: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=80aaa991-eaeb-3aae-8555-590cb1a2faf7 (Accessed: 4 August 2024).

[5] Losses on investments can be offset against ordinary income such as wages, thus reducing a TP’s assessable income and lowering overall tax paid

[6] Loan to Value

[7] Parliamentary Budget Office (2024) Cost of Negative Gearing and Capital Gains Discount Tax, advice provided to Adam Brandt MP 17Jun 2024.

[9] The latest average weekly earnings for all employees by the ABS for May 2024 is $1,480.90, which makes the average annual wage $76,960.

[10] Kohler, A. (2023) The Great Divide Australia’s Housing Mess and How to Fix It; Quarterly Essay 92. Black Inc. Available at: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=80aaa991-eaeb-3aae-8555-590cb1a2faf7 (Accessed: 4 August 2024).

[11] Ibid

[12] ABS Building Approvals https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/building-and-construction/building-approvals-australia/latest-release

[13] Data only from 2016-2023, we used an average of that dataset for the prior years.

[14] Dailey, J, and Wood,D. (2016) ‘Hot Property Negative gearing and capital gains tax reform’. Grattan Institute.

[15] Falinski, J et.la (2022) ‘The Australian Dream: Inquiry into housing affordability and supply in Australia’. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue, Australia

[16] Semi-Annual

[17] https://www.apra.gov.au/news-and-publications/apra-announces-plans-to-remove-investor-lending-benchmark-and-embed-better

[18] Goods and Services Tax

[19] Global Financial Crisis

[20] Kevin Rudd

[21] https://www.news.com.au/finance/real-estate/first-home-boost-will-end-in-june-rudd/news-story/eed70a7bc5626e3df15e5b29c0892124

[22] Eslake, S. (2013) ‘Australian Housing Policy: 50 Years of Failure’, Submission to the Senate Economics References Committee.

[23] Kendall, R., Tulip, P., The Effect of Zoning and House Prices, Research Discussion paper 2018-03, Reserve Bank of Australia 2018

[24] NIMBY: Not In My Back Yard

[25] https://www.pm.gov.au/media/new-funding-deliver-more-homes-australia#:~:text=The%20Albanese%20Labor%20Government’s%20Homes,turbocharge%20construction%20of%20new%20homes.

[26]https://onefinaleffort.com/auckland#:~:text=In%20November%202016%2C%20Auckland%20upzoned,Auckland%20Unitary%20Plan%20(AUP).

[27] Greenaway-McGrevy, R. and Phillips, P.C.B. (2023) ‘The impact of upzoning on housing construction in Auckland’, Journal of Urban Economics, 136. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2023.103555.